Three years since the official start of the Ukraine war, I often find myself engrossed in geopolitical analyses or watching podcasts dissecting the conflict. It’s not surprising—especially for those of us in international relations or security studies—that we feel the need to stay informed. Yet, as I consume this endless stream of expert discussions, I cannot escape a growing discomfort: war has become a detached intellectual exercise, stripped of its most profound reality—human suffering.

My late friend and colleague, Prof. Zdravko Grebo from Bosnia and Herzegovina, once said, “The war begins when the media stop telling the names of the victims and start sharing numbers instead.” Numbers that grow and grow, until the dead become mere statistics. His words resonate deeply today. Death has been normalized—not only in Ukraine but across the globe. We rarely hear the names, faces, or stories of those who suffer.

I think of Robert Fisk, the late journalist whose humane and ethical reporting stood out. He didn’t just report on conflicts; he gave voice to the voiceless. Fisk visited hospitals and morgues, sat with families who had lost everything, and told the personal stories of children, women, and elders killed or maimed by war. He brought the dead back to life through his words, helping us see their humanity and mourn their loss.

During the 2003 Iraq War, I translated Fisk’s columns every day for my mother, who didn’t know English. Often, I would find myself sobbing as I read his vivid accounts, overwhelmed by the enormity of the suffering he described. My mother, worried for my well-being, asked me to stop. But I couldn’t—because Fisk’s mission was clear: to wake us up to the horrors of war and remind us that behind every number is a life, a family, a story.

Today, such journalism feels rare. In academia, we are encouraged to be “objective,” to keep emotions at bay. Empathy, solidarity, and pain have been exiled from the halls of knowledge. Scholars analyze wars with clinical detachment, producing cold, calculated insights that often neglect the human cost.

When Yugoslavia disintegrated in the 1990s, I sought refuge in peace studies. Scholars like Johan Galtung, Håkan Wiberg, and Jan Øberg taught me that peace research must balance reason with compassion. Johan often likened peace researchers to doctors, who must empathize with patients while diagnosing and treating their suffering. This wisdom remains a guiding light, but it feels increasingly absent in today’s intellectual discourse.

As a professor and public intellectual, I follow media outlets, podcasts, and Substack profiles daily. While I deeply respect many of the world-class thinkers offering alternative perspectives on conflicts from Ukraine to Syria, I am growing weary. Even when they acknowledge genocide or the threat of nuclear war, the discussions remain rooted in geopolitics—states’ interests, power struggles, and military strategies.

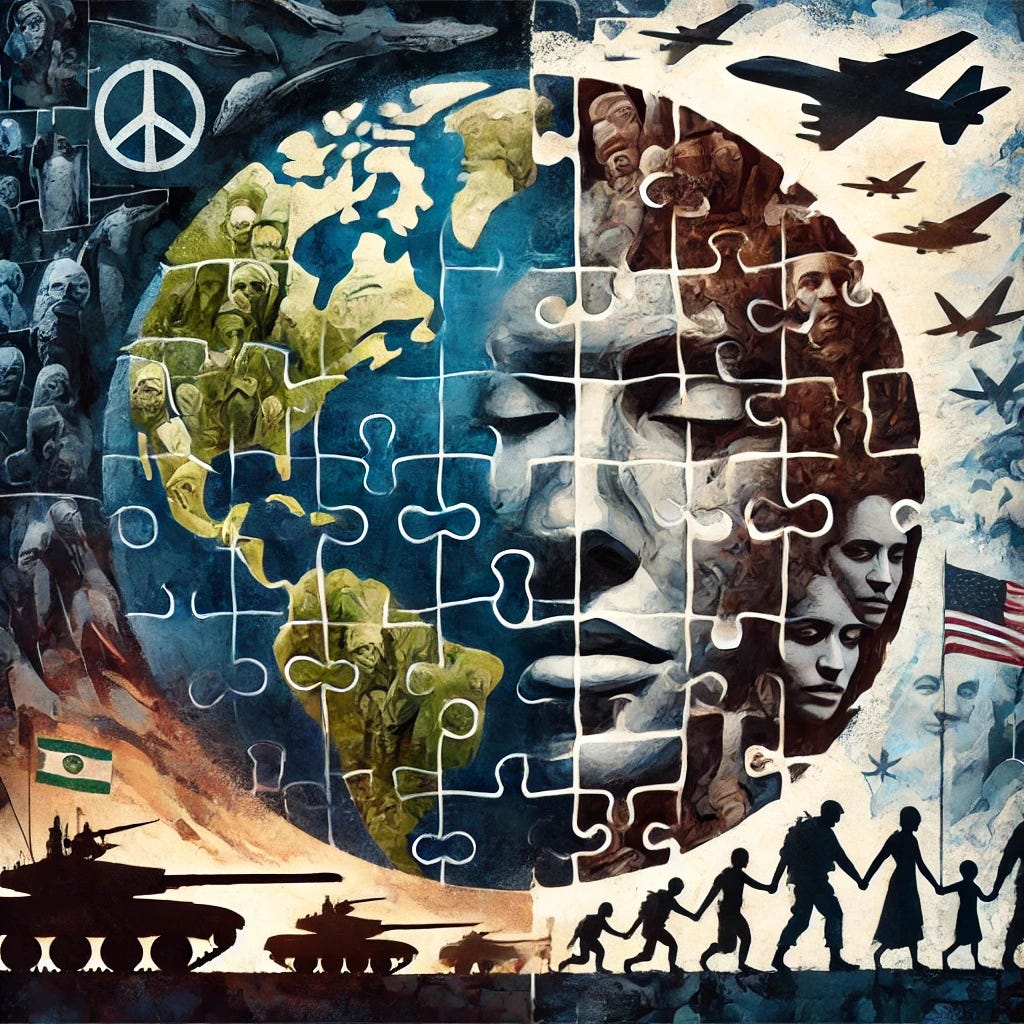

Maps, military maneuvers, and political statements dominate the narrative, while ordinary people remain invisible. The horrors of war are reduced to chess moves on a geopolitical board. The stories of children, families, and communities are lost amidst the grand analyses of imperialism and hegemony.

We are told that understanding the “big picture” is essential. And yes, geopolitical analyses are crucial for grasping the dynamics of power and conflict. But at what cost? Have we, as experts, become so consumed by the abstract that we’ve forgotten the concrete—the lives destroyed by these very dynamics?

Sometimes, a video on social media pierces my intellectual armor, shattering my carefully constructed detachment. It reminds me that behind every “advance” or “retreat” on the battlefield are people like us—parents, children, friends—living and dying in unimaginable pain.

This is not just a critique of others; it is also a reflection on my own complicity. I, too, have participated in discussions that prioritize analysis over empathy, reducing war to a theoretical exercise. How can knowledge be of value if it cannot save lives?

We need to break out of our echo chambers and our bubbles of quasi-activism. The world doesn’t need more analyses or think pieces; it needs action. It needs an anti-war, anti-nuclear, and perhaps even anti-fascist coalition to confront the forces that perpetuate violence.

History has shown that silence and inaction in the face of rising fascism and imperialism lead to catastrophe. If we continue to prioritize intellectual vanity—measured in likes, views, and followers—over meaningful engagement, we are complicit in the suffering we claim to oppose.

It is time to refocus our efforts. We must tell the stories of the nameless and the voiceless, advocate for their rights, and fight against the systems that perpetuate their suffering. Let us remember that behind every statistic is a human life—and let that knowledge guide our work.

Још један одличан текст, хвала Вам.

Пратим рат у Донбасу од првог дана. Не од 2022, него од 2014. За разлику од наших ратова где је запад са задовољством запалио ломачу коју смо ми сами спремили из глупости и наивности, у Донбасу је са задовољством донирао дрва и бензин и вршио обуку у бацању шибице. И потпуно се слажем са онима који кажу да се кад погину по један Рус и један Украјинац то "бодује" као 2:0 за запад.

За цинизам и равнодушност према истребљивању беспомоћних становника Газе и Сирије немам речи. Док се ситуација у Донбасу жустро правда ничим изазваном Руском агресијом, ово се једва и спомиње. По принципу "ако није било на телевезији, није се догодило". Колективни запад није далеко одмакао од колонијалних ратова XVIII и XIX века, мада данас имају тоалете за сексуално неопредељене и запошљавају по етничком и расном кључу.

There are so many stories that do emerge, but the audience for them seems to be limited. Many people, even my own family and friends and colleagues, often push the reality aside as "complicated", and following the "legacy media" (this seems to be the new description!)makes me frantic to see the lies and their repetition unchallenged.