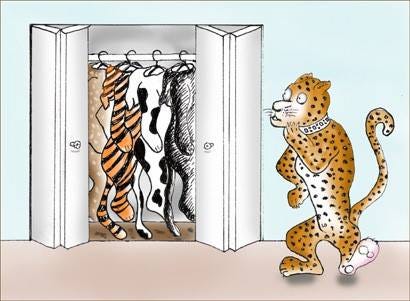

Rubio’s reasoning as a reason for optimism? A leopard cannot change its spots!

My reflection to Glenn Diesen's analysis

Glenn Diesen commands well-deserved respect among scholars of international relations and security. While his work merits serious engagement, this does not oblige us to uncritically accept his conclusions. Diesen himself, I suspect, would welcome rigorous debate—a necessity in Trump’s political arena, where magical thinking and performative brinkmanship often overshadow reason. Moreover, both Glenn and I are part of the network of associates at the

(TFF) in Lund. I am convinced that we share the same values and principles, though we can certainly analyze events through different perspectives.Trump ascended to power on a wave of disillusionment: the dashed hopes of marginalized Americans and the Democratic establishment’s failure to inspire. Yet his campaign was a carnival of populist theatrics, mutual vilification, and hollow promises. The few voices advocating systemic change—Jill Stein and other “non-electables” dismissed by bipartisan media—were drowned out. Weeks into Trump’s presidency, analysts still scramble to decode his erratic governance. We parse contradictory executive orders, dissect rambling speeches, and piece together shards of policy from the debris of his electoral circus. A self-styled “peace president” eyeing a Nobel Prize, Trump oscillates between incoherent diplomacy and reckless militarism. His administration’s logorrhea and policy whiplash reveal a leader unmoored from strategy.

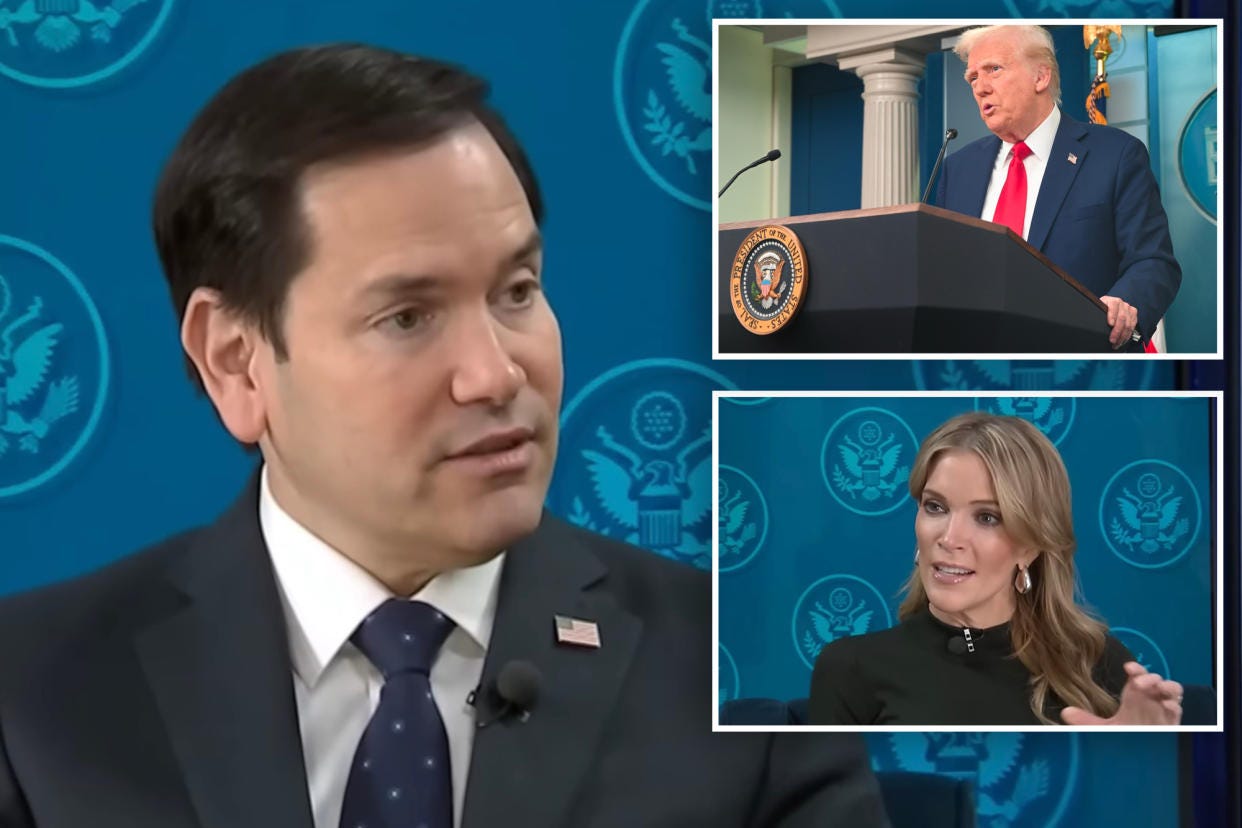

Understandably, for those of us outside the United States, global security and the prospects for war and peace are our primary concerns. Our esteemed colleague, Prof. Glenn Diesen, offered an insightful and thought-provoking analysis just a day after Secretary of State Marco Rubio's interview with Megyn Kelly on January 30, 2025. Diesen suggests that Rubio may have (whether intentionally or inadvertently) signaled the beginning of the end of America's hegemonic security strategy. As he noted, “Rubio recognized that unipolarity, having one center of power in the world, was a temporary phenomenon that has now passed.”

Indeed, Rubio said that “it’s not normal for the world to simply have a unipolar power. That was not – that was an anomaly. It was a product of the end of the Cold War, but eventually you were going to reach back to a point where you had a multipolar world, multi-great powers in different parts of the planet. … (W)e were the only power in the world, and so we assumed this responsibility of sort of becoming the global government in many cases, trying to solve every problem”.

Diesen interprets this as a nascent acceptance of America’s diminished hegemony, even suggesting cautious optimism. But as a scholar from a region scarred by U.S. “benevolent hegemony,” I am less sanguine. My country’s identity was forcibly rewritten under Trump’s first term—a NATO accession deal on name change (from Macedonia to North Macedonia) brokered by Washington and Brussels, masquerading as a bilateral accord with Greece. The Macedonian public’s resounding referendum rejection of this identity erasure was dismissed as “Russian meddling,” as though small nations lack agency to resist geopolitical engineering.

Perhaps I am more cynical than my colleague from Norway — and understandably so, given that I come from a region that has endured the full brunt of the U.S.'s self-appointed role as the world's policeman. This includes the forceful reconfiguration of my country’s name and identity, ostensibly to secure NATO membership through a treaty with Greece. However, it was an open secret that this agreement was crafted not in the Balkans but in the offices of the Brookings Institution, with Balkan leaders merely dancing to the tunes orchestrated by Washington and Brussels. Let us not forget that this identity and constitutional engineering occurred during Trump's first mandate.

Determining the precise moment when unipolarity ended and multipolarity emerged is undeniably challenging. One key factor, however, was Washington's tendency to cry wolf, conjuring threats and external influences even where none existed. For instance, the very fact that the Macedonian nation said clearly NO to the name change treaty on a national referendum was interpreted as a “result of negative Russian influence”!? As if a small nation may not have brains and heart to recognize its brutal “transformation” against the people’s will!

Turning to Rubio's interview, some American commentators remarked, “Interestingly, it’s the first time I’ve ever heard Rubio speak with reasoned intelligence.” Diesen interpreted part of Rubio’s remarks as an acknowledgment of the unipolar world order's demise after the Cold War and the need for the U.S. to adapt to multipolar realities. Diesen concluded his analysis with a section titled A Reason for Optimism, suggesting that there may be a growing willingness within the White House to retire the temporary project of unipolarity. The emphasis here is on “temporary”—a word that underscores the self-delusion of the U.S., which not only lies to itself but also assumes that others are gullible enough to trust it after decades of hegemonic interventions since the so-called “end of history.”

Diesen’s optimism falters under scrutiny. Rubio’s interview, read in full, drips with Orwellian doublespeak. His nod to multipolarity coexists with chest-thumping exceptionalism, echoing Trump’s delusion that “the big stick” still terrifies a decolonizing Global Majority. Radhika Desai aptly critiques this duality. In a recent public event, she said: „President of the US at a time when its power was rising, Theodore Roosevelt is famous for repeating the aphorism ‘speak softly and carry a big stick’. In the age of declining US power, clearly, Trump has the opposite as his motto: speak loudly, speak much, and frantically wave your diminished stick. For this is what he has been doing. Naturally, the world is trying to parse through what his threats mean.“

Let me remind us that the US cannot simply “adjust to multipolar realities” – because the multipolarity is a direct reaction to all the evil and slaughters committed under the US flag! If they want to become a normal/ordinary partner in the multipolar world they will have to make some soul-searching and express remorse for all the states they have “democratized” by bombs and “colored revolutions”. Otherwise, the Global Majority would still look at them as a rogue state, a failed state (to quote Chomsky). Trump is still surrounded by hawks (including Rubio, of course). He wants to spread peace on earth by one hand, while preparing for ethnic cleansing of the Palestinians on the other. He wants to extort money from his poorer allies (Macedonia, included) while talking about cooperation. All we can hope for is that he will soon fail and will eventually shoot in his own leg. Chris Hedges is so far one of the few American intellectuals who see that Trump is not a Savior and that the working class should start organizing for a change not of a president but of the rotten and militaristic system.

By now you got my point: I am afraid I see no reason for optimism. Even the remaining (not quoted) part of Rubio’s interview was exactly in the line of American exceptionalism and the megalomaniac plans of his boss. The interview in its totality could be read as Orwellian doublespeak. Or as Radhika Desai put it recently in a webinar: instead of speaking softly and bearing a hard stick, Trump is hitting hard with his speeches at the same time while waving with this stick (the threats to bring Putting to his reason, for instance). Under such circumstances, we have to deal with a “wild card” all the time during the next four years. This is the case, of course, only if we attach so much influence to the personality of Trump and his loyalists. The old/new US President is hardly aware that the world has dramatically changed since his first mandate, let alone since the emergence of BRICS and other multipolarity traits. He is still trying to project his machoistic “big stick” and believes that others are sheep who would be obedient. But let’s be fair: he is not the only US president to be drunk out of the greatness of his state and leadership, and this detached from reality.

Even if Trump believes he can navigate the emerging political multipolarity, he remains a bully when it comes to economic multipolarity. His understanding of global affairs is akin to that of a poorly informed student—he once mistakenly included Spain in the BRICS countries and threatened to impose tariffs of up to 100% as punishment. This level of ignorance is hardly surprising, as U.S. empire managers are rarely known for their knowledge, coherence, or competence. Sooner or later, they will face an economic reckoning, just as the Ukraine war is likely to end as another U.S./NATO military debacle. The West, whether viewed from Washington or Brussels, remains dangerously delusional.

Rubio’s rhetoric about the alleged necessity for the U.S. to reclaim its role as world policeman (as if there were no United Nations or other international organizations!) continues the bizarre pattern established by Trump’s tweet of Jeffrey Sachs' Cambridge Union speech Q&A, where Netanyahu was labeled as "a deep dark son of a bitch." That same "son of a bitch" will be the first foreign dignitary to visit Trump in the White House, despite a warrant from the International Court of Justice. Should we expect positive developments, or perhaps instructions on how the new bulldozers (not diplomatic ones, but real ones waiting to "clean up" Gaza) will be used? Let's not fall for false optimism. We must brace ourselves for Trump 2.0, who will remain unrestrained by international law or any goodwill to leave behind a positive legacy. Instead, he is more likely to embody an American Nero.

Occasionally, I have to admit, we might be puzzled by some of his moves and interviews. But don't forget to ask yourself a simple question: has the U.S. ever assumed responsibility for anything other than its own self-interest? Why is there no Willy Brandt in America? The notion that the U.S. sought to foster global governance for the good of the world is simply self-serving hypocrisy.

In the Balkans we have an old saying: “A wolf changes its fur, but never its temper.” The English equivalent—“a leopard cannot change its spots”—aptly captures U.S. intransigence. Until America confronts its legacy of violence and exceptionalism, optimism is not just premature—it’s complicity.